|

Helpful hint: click on labels and photos for even more information!

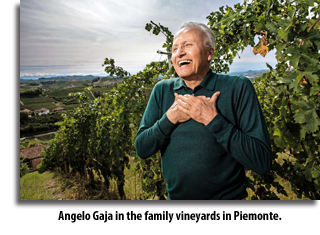

Angelo Gaja of Barbaresco, now a young 75, jolted the entire Italian wine industry into the Big Leagues. Angelo Gaja of Barbaresco, now a young 75, jolted the entire Italian wine industry into the Big Leagues.

From the ’60s on, he defied his father and dusty Piemonte traditions, introducing French vines and barrels, green harvests, low yields, modern winemaking and better corks.

He created “cru” Barbarescos – Sorì San Lorenzo in 1967, Sorì Tildìn in 1970 and Costa Russi in 1978 before expanding into Montalcino and Bolgheri in Tuscany.

His wines today equal the icons of Bordeaux and Burgundy, commanding stratospheric prices. His label says GAJA in capitals, and rightly so!

The firm is now co-run by daughters Rossana and Gaia. And Gaia, based in Barbaresco, (pop. 650) says global warming is a major preoccupation.

“We’re worrying about all the warm summers we’re having. We’ve had to reconsider how wemanage the vineyards. We opened our doors to consultants and started to change things. “We’re worrying about all the warm summers we’re having. We’ve had to reconsider how wemanage the vineyards. We opened our doors to consultants and started to change things.

“Climate change doesn’t always mean warmer, although 2015 was very hot. It means unreliable and abnormal seasons that are more stressful for the plants, and new plant diseases.

“We now cut the new bud wood on the vines every year instead of once every 5 years. Smaller cuts help the plant live longer, with fewer infections. We pioneered that, and it’s been adopted at Chateau Latour and by the Moet group, too.

“All our Barbaresco sites are hilltops facing south, historic for growing Nebbiolo but the soil was getting drier and warmer, harder to keep alive. Now we nourish it with our own compost – cow manure that’s re-fermented, with worms added to digest it further. This adds yeasts, micro-elements and good bacteria to the soils.

“Another problem was vine moth larva eating the berries. We’ve experimented with sexual confusion using pheromones and persuaded our neighbors, 60 farmers in the co-op nearby covering 700 hectares, to use this and not pesticides.

“Our goal is healthy resilient plants that can adapt and defend themselves. We replanted 250 cypresses and a mix of local plants, grasses and flowers the vineyards and we only plow every four years.

“Flowers attract life and we set up 40 beehives. Bees carry a food vital for yeasts, so you can have more diversity of yeasts. The bees are also a bio-indicator of the environment.

“The vine tops used to be cut and so was the grass. Back then we needed to take the water out of the soils after cold wet vintages. Our solution was cut the grass and it takes out more water to grow again.

“We also needed more sugar in the grapes to get more alcohol: cutting the vine encourages new leaves that are energetic solar panels creating more sugar. Today we have the opposite problem. We need to keep humidity in the soil so we don’t cut the grass, we roll it and it creates a blanket that’s not drinking water and under that it’s soft, hot and moist. Perfect.

“We don’t top the vines now. We twist the tops and because plants are intelligent living beings they start to focus on ripening the grapes. With young high-vigor vines we introduce barley, grain and cereals between the rows to reduce the power of the soils and let the plants grow more slowly.

Gaia tells how her father coaxed vineyard workers in Communist-leaning Bolgheri to accept earthworms from California rather than Italy “because the US worms are red and anyway we couldn’t get any from Russia…”

“In the winery there’s more use of lees (spent yeasts) as antioxidants during the barrel aging and adding grape stems during the fermentation. The vineyard workers are encouraged to live beside the vineyards and tend the same rows of “their” vines for generations.

“I can’t say all this will make our wines better but we try and we believe,” concludes Gaia. “Our innovative spirit comes because we’re from Barbaresco, a great vineyard but always considered number two (to Barolo) so you had to be innovative if you wanted to be the best.

“We’ve always been respectful of tradition. We’ve keep our own style inspired by biodynamics. We’re proud of what we’ve tried and we keep our identity very clear.”

Some GAJA wines for you to try:

- GAJA Piedmont: Rossj Bass 2014 (Chardonnay/Sauvignon Blanc)(92) $94.99

- Gaia & Rey 2013 (Chardonnay) (93) $264.99

- Sito Moresco 2013 (Nebbiolo, Merlot, Cab) (92) $64.99

- Dagromis Barolo (93) $98.99

- Barbaresco 2012 (92) $264.00

- Conteisa (93) $290.00

- Sperss (94) $320.00

- Ca’Marcanda, Bolgheri, Tuscany: Vistamare 2013 (Vermentino, Viognier) (92) $54.99

- Promis 2013 (Merlot, Syrah, Sangiovese) (92) $53.99

- Magari 2013 (Merlot, Cab Sauv, Cab Franc) (93) $73.99

- Ca’Marcanda 2011 (Merlot, Cab Sauv, Cab Franc) (94) $190.00

- Pieve San Restituta, Montalcino, Tuscany: Brunello 2010 (92) $84.99

- Rennina Brunello 2010 (92) $179.99

- Sugarille Brunello (94) $189.99

Contact the Stem Wine Group at (416) 548-8824.

Wine collectors swoon at the ageability of elegant Bordeaux, Barolo, Madeira and Port. Rarely is Spain on the radar.

However, in its 125 years of expertise, Bodegas Franco-Espanolas has always carried the flag high for Rioja. However, in its 125 years of expertise, Bodegas Franco-Espanolas has always carried the flag high for Rioja.

After France’s vineyards were destroyed by the phylloxera bug, French wine broker Frederic Anglade Saurat and local partners set up shop in Logrono in 1890.

Almost immediately, Franco-Espanolas became one of Rioja’s most exciting new wineries. The reds were cutting edge and Saurat’s influence on Rioja persisted well into the 20th century.

Ernest Hemingway, a lover of Spain and its vino, hung out at the Paternina winery, championing its Banda Azul to international acclaim, and at Franco-Espanolas. He visited after winning the Nobel for Literature in 1954 and was a huge fan of their everyday red, Diamante.

He would have loved the tasting I attended.

The flagship wine is Rioja Bordon, named for its kinship with the graceful, medium-weight, complex reds of Bordeaux. In other words, love claret, love Rioja.

Saurat’s concept was to marry Bordeaux techniques with Rioja fruit emphasizing terroir and restraint.

The 2015 result for Canada is the availability of the 2005 Rioja Bordon LCBO 428060 and soon the 2006 in our stores, for the attractive price of $22.95.

But first, the ageability issue. Here’s the DNA:

- The 1982, fully evolved, with hints of toffee, Sherry or Tawny Port yet full of wild strawberry, blueberry and vanilla, silky tannins. Holding well.

- The 1985, soft red fruit, saddle leather, nutmeg and dried cherry with delicate acidity, classic midweight red, perfect with lamb and pork. Still vibrant.

- The 1994, deeper ruby red, with new leather, richer and more full bodied, showing cherry-strawberry, dried tobacco and blueberry notes. In perfect fettle.

- The 1995, bigger, more fleshy with smooth tannins and fruity acidity, sage and anise notes, less evolved and good for years more cellaring.

- The 2001, deep color, ripe black and red fruit, sandalwood and a melange of black raspberry and vanilla, chewy tannins and sturdy structure for long aging.

- And the 2005, a classic Rioja, fresh, full, fragrant and bursting with berry fruit – wild strawberry, black cherry, dried raspberry with a whack of vanilla. Balanced and intense with hints of new leather and wood smoke (92). Drinking well and will reward cellaring for 10 years.

- The 2006, when the 2005 has sold through, more new leather notes, vanilla, dates, marzipan and toasty oak, intense and enjoyable now to 2025 (91).

- The 2005 is available in the Signature Collection (Spanish wines category) for $22.95, LCBO 428060.

- The 2009 will be released next March at $18.95.

Winemakers say ‘if we save the old grapes, the old grapes will save us,’” according to Arnaud Daphy of Wine Mosaic, a French group dedicated to conserving indigenous varieties. “There’s new interest from wine lovers and sommeliers in off-the-beaten path wines.”

While 10,000 grape varieties exist across the globe, only 1,500 are used to make wine, and a mere 30 varieties produce 70% of all the wine consumed worldwide,

The phylloxera plague in the nineteenth century decimated native vineyards in Europe. In the twentieth century, many varieties were ripped out and replaced by internationally marketable vines.

In France’s Languedoc region, old Carignane and Cinsault vines were replaced by Syrah. In Sicily, Nero d’Avola made way for Cabernet Sauvignon. Some went extinct, while others like Persan in Savoie have under a hectare of vines left.

That’s why regions like Sicily, Tuscany and Piedmont are experimenting with heirloom vines.

“Some of them – Alzano, Nocera, Vitrarolo – are on mountaintops, and nobody was cultivating them,” says José Rallo of Donnafugata, a leading winery in western Sicily experimenting with 19 relic varieties.

“We believe that with special care and new technologies, some of these ancient varieties can become great wines.”

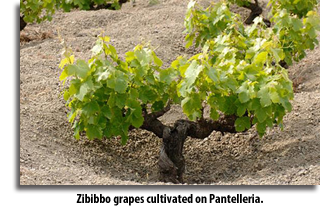

On the nearby island of Pantelleria, her vineyard workers have been carefully harvesting a variety of Zibibbo grapes from vines at risk of extinction. Also known as Muscat of Alexandria, and thought to have originated in the Egyptian city, this grape is used to make passito wines, some of Italy’s most prized dessert wines.

For five years, scientists have been searching for endangered strains of this ancient vine, carefully removing plants from overgrown estates and remote mountains in Spain, Italy, Greece and France and cultivating them on test plots on Pantelleria.

Now, the first fruits of their labor have just been harvested from 2,117 vines scattered across this remote volcanic island.

“These biotypes are at risk of disappearing, but we believe that their genetic patrimony can help us enhance existing and new Zibibbo wines,” said lead scientist Attilio Scienza, professor of viticulture at the University of Milan. “These biotypes are at risk of disappearing, but we believe that their genetic patrimony can help us enhance existing and new Zibibbo wines,” said lead scientist Attilio Scienza, professor of viticulture at the University of Milan.

Experts believe these vines are some of the oldest in existence. The Phoenician goddess of Carthage, Tanit, is said to have seduced Apollo by serving him Muscat of Alexandria from the island. Arab traders who brought it to Europe valued the variety as a table grape – the word Zibibbo comes from an Arabic word meaning “raisin”.

“Wherever the Arabs went, Zibibbo went with them,” says Antonio Rallo, president of the Sicilia DOC Consortium.

“The Sicily region, together with the University of Milan, searched the entire Mediterranean basin for Zibibbo and found 33 different biotypes: nine on Pantelleria, one in Calabria, 10 in Greece, 10 in Spain and three in southern France.”

Pantelleria’s coastline is battered by sea spray and high winds in winter. To protect the plants, the vine bushes are buried low in hollows along terraced plots divided by lava drywalls. Centuries-old ungrafted vines still produce fruit, shielded from pests and plagues thanks to the island’s isolation. Pantelleria’s coastline is battered by sea spray and high winds in winter. To protect the plants, the vine bushes are buried low in hollows along terraced plots divided by lava drywalls. Centuries-old ungrafted vines still produce fruit, shielded from pests and plagues thanks to the island’s isolation.

The researchers say the rootstock is resistant to drought and salinity, but there are important variations. “In Turkey, France and Greece, these grapes were destined for wine, while in other areas they were cultivated as table grapes or raisins,” says Professor Scienza.

The team plans to make and compare five different wines. Subtle differences in the grape’ sweetness, aroma and other characteristics are already noticeable, but the wine will show their full potential.

Please take me back to the top of the page!

Please take me back to Being There!

|

|

|